I had never heard of this novel until I read about it in Stephen J. Bodio's illuminating

Sportsman's Library, but his praise convinced me to run down a used copy and read it. I bogged down half way through the first time: I kept feeling I was missing something. A year later, I picked it up again and persevered, becoming more and more interested in this novel's power of suggestion, a power the more unusual because it derives less from what is said than from what is left unsaid.

The novel is narrated by Aleck Maury, a surviving representative of a socially privileged, literate but largely unintellectual Southern culture. Maury apparently was born some time during or shortly after the Civil War at Oakleigh plantation in Louisa County, Virginia. Just as reading most of Jane Austen you'd never know the Napoleonic Wars were in progress, so in

Aleck Maury, Sportsman you'd hardly realize the Civil War had been fought.

Aleck Maury's mother had died while rocking baby Mary to sleep, so Aleck, the second youngest of five, was brought up by his eldest sister. Aleck Maury's father did little but blame the parlous times for the ever-declining yields of his plantation, its soil depleted by successive crops of tobacco. Impoverished from gambling, his father passed the time by writing blank verse, reading Classical literature, and declaiming poetry to his children.

When Aleck was eight, his father began to teach him first Latin and then Greek. He made no effort to accommodate his instruction to a child's understanding. One of the novel's memorable moments is Maury recalling his father fixing his eye on him when he mistranslated a line of the

Aeneid, saying sternly, "

That, sir, is a dative." Maury became good at Latin and Greek, and after graduating from the University of Virginia and working hand-to-mouth as far as Seattle and San Francisco, he eventually returns, not to Virginia, but to Tennessee to become a school teacher. Almost by default, Maury adopts the vocation of teaching Classics. He persists in this endeavor until late middle age, and one of the many unvoiced but remarkable aspects of this novel is that its narrator seems to have learned almost nothing from the material he taught to others.

Maury's vocation may be teaching Classics, but that is not remotely his avocation. From his first experience as an eight-year-old on a possum hunt with Rafe, hunting and fishing afforded him the most intense experiences of his life. By hunting I mean bird shooting, not, as the English would have it, riding to hounds (which Maury tried and didn't like especially), and by fishing I mean angling for crappies, bream, and bass with fly or bait. Bird shooting and fishing offer him an escape from himself, and Gordon is careful to leave it to the reader to judge whether that alternative is a viable, let alone a sufficient, one. Ironically, the closest Maury comes to uniting his vocation with his avocation is writing down on the flyleaf of his first copy of the

Aeneid his fishing mentor's recipe for making dough balls to catch suckers.

We learn more about Maury's affection for his muzzleloading Greener shotgun than we do about his favorite writers. The only time anything from Classical literature becomes important to his life is when Maury muses he'd like to hear his student Molly Fayerlee read aloud some lines from Horace. Typically, Gordon doesn't give the source, but it's Ode I.9:

Quid fit futurum cras, fuge quaerere; et

Quem fors dierum cunque dabit, lucro

Adpone; nec dulces amores

Sperne puer, neque tu choreas . . .

In George F. Whicher's translation, one I like to think Maury would have appreciated:

Pry not into the morrow's store;

Thy profit doth advance

By every day that fate allots,

So, lad, improve thy chance,---

Ere stiff old age replace thy youth,--

To love and tread the dance.

Apparently Molly did read those lines aloud, and apparently that led to his marrying her (or, possibly, her marrying him) in 1890: Caroline Gordon routinely omits seemingly relevant details like these.

Some years afterwards, following moves first to Mississippi and then to Missouri, misfortunes befall Maury and his family. Their son dies from an accident while swimming, Molly and he grow a bit apart, and then Molly dies while undergoing surgery (perhaps for cancer; again, we do not know). Maury grieves after his own fashion, putting aside hunting and fishing. Soon after that, he is asked to resign from the college where he teaches. Suddenly he is free, and it's ironic that at first he has absolutely no idea what he wants to do. Depressed, he begins to realize that he's getting old.

He spends the next few years attempting to establish a fish farm but is not especially successful. For the very first time in his life, drifting about on the still waters of Lake Lydia, he does contemplate his own death, but, unsurprisingly, his

memento mori doesn't reach any resolution. He remains depressed and at loose ends. On a whim he decides to go to Florida and fish--again, not a successful experience.

In the last chapter, his daughter Sally and his son-in-law Steve suggest he come to live with them. The three of them begin looking for a suitable house near Caney Fork, Tennessee. The first part of this chapter serves primarily to demonstrate not merely how old-fashioned but how old Maury has become: their youthful energy highlights his decrepitude. He's fat, his legs hurt, and he quickly becomes winded. Sally's contemporary slang seems to him altogether inappropriate (much, perhaps, as Maury's mode of addressing blacks, young and old, seems inappropriate to our own sensibilities). Stiff old age has indeed replaced his youth.

Then, everything changes for the better. Hearing about the fishing to be had in Caney Fork and then seeing the river itself revive Maury's spirits remarkably. While Sally and her husband are debating about where to live, Maury quietly sneaks on a bus and takes off to go fishing in Caney Fork. He may perhaps have finally realized the wisdom of the Englishman who years before taught him to cast a fly. Back then, Colonel Wyndham had pursed his lips reflectively and told Maury: "You're young and you don't realize it yet, but there isn't time enough . . . There isn't time enough."

Habitually unreflective, Maury doesn't grasp the significance of Wyndham's insight, and he doesn't even recall it when, a number of years later, he once again sees Wyndham, now aged ninety, gamely stumbling down to a river to fish. Even at the very end of the novel, when he realizes in surprise that he'd just turned seventy a few days before, it is impossible to say whether Maury decides to seize the day and to make the most of his remaining time, or whether he simply decides he wants once more to go fishing. A lesser novelist would have been underlining the theme of

carpe diem every time the narrative would allow it. Caroline Gordon, thankfully, is content to just make a slight gesture toward it.

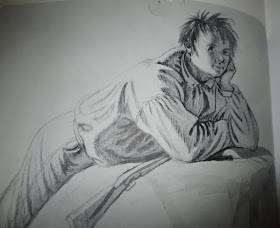

This is a self-portrait by a sportsman who has resolutely remained focused on the surface of life, but Caroline Gordon has made brilliant use of what in graphic art is termed negative space: What is not said by Aleck Maury, Sportsman, is just as important as what he does say.